Lowering the marginal cost of digital projects

or

We're not as cheap as you think, but we make it up in volume

Once upon a time I was involved in a project to select a content management system for a number of NHS organisations. After much brochure reading, vendor meeting and metaphorical tyre kicking, we eventually shortlisted a few systems for detailed investigation. About 50 percent of these systems were commercial and proprietary, the other 50 percent were open source.

This was a year or so before open source digital publishing systems (notably WordPress) hit the mass market. So the open source waters were slightly uncharted and the usual Fear, Uncertainty and Doubt (FUD) was being bandied about by the proprietary vendors. Lack of support, maturity, and general ease of deployment and use, none of which turned out to be real problems in the end.

But at the same time the open source proponents were issuing their own brand of FUD, mostly about cost. “It’s open source so of course it’s cheaper”, without qualifying how that might be true. This didn’t cut much ice with management, who pointed out to me at some length we were a predominantly Microsoft shop, there would be significant retraining costs associated with moving to the preferred open source system, and the preferred proprietary system was actually pretty cheap.

I’ve seen unqualified cost arguments made many times in favour of open source software, both then and now, and the rebuttal is often the same. Often, open source systems actually don’t have a compelling one-off cost advantage. Over the lifetime of a project, a single license cost may be an insignificant percentage of total cost, especially if the open source system requires retraining, additional customisation, or is harder to deploy and maintain.

So I went and did some homework to qualify the costs. It turned out we could get all our staff trained on the open source system for about three times the cost of a proprietary license for a single website. Not so compelling yet… except we were planning to build about ten sites. And of course we didn’t have to buy open source licenses for all those sites. Once we’d paid for the initial training that was it. So the marginal cost (and I may be misusing that term - feel free to correct me in the comments) of the open system was lower. Additional deployments and work would be very low cost. And because we were scaling out the overall cost to the organisation was much lower.

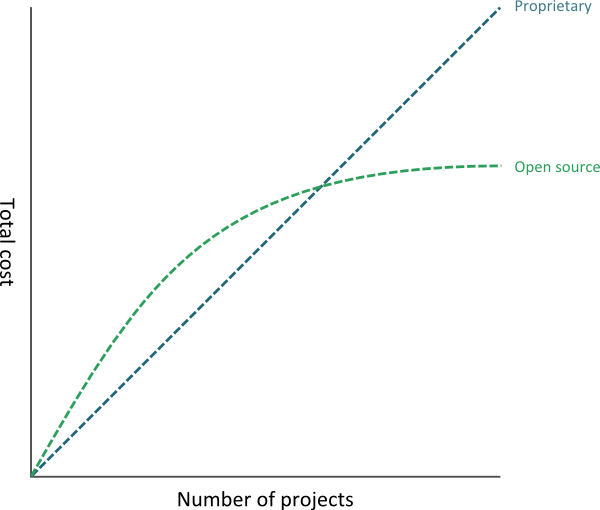

Plotted on a graph, it might look something like this:

The actual figures were something like this:

| Open source | Proprietary | |

|---|---|---|

| Training | £6000 | £0 |

| 10 licenses | £0 | £20,000 |

| Total | £6000 | £20,000 |

Other costs (servers, connectivity, etc) were the same for both. We were deploying on Windows in both cases though we could have squeezed some more money out by deploying on an open source operating system such as Linux.

Of course this model is simplistic. In the NHS, many software licenses are purchased in bulk and their marginal cost is low. On the other hand this wasn’t one of those products, and there’s an awful lot of artificial complexity imposed on some technology decisions. Sometimes a simple decision-making process is what’s needed, particularly in relatively small, low cost and short term projects.

Fast forward a few years, and I see similar things happening in cloud computing and DevOps. Say you want to scale horizontally (deploy many more of the same things), or you want to quickly bring up additional nodes on demand, or you want to rapidly and automatically build and tear down environments. Maybe you have to invest up front in training or configuration, but that investment pays off when you can deploy 10 (or 100, or 1,000) new things with almost no additional cost or effort.

Low marginal cost is an important benefit of open source software, and a good tool in a business case. Open source vendors should make more use of it, rather than just repeating the mantra about open source being cheap.